Rather than an exhaustive list, I’m sharing my favorite books I read in 2025. These are books that stuck with me over time (the first few were read over the first couple months of the year), books that answered questions I’ve been pondering or provided some form of comfort or insight. Everything is connected, and history isn’t so distant. I saw a lot of today in books about the past.

1. The Summer of the Great-Grandmother by Madeleine L’Engle

I lost my last living grandparent, my paternal grandmother, in 2024, and I picked this book up at the thrift store that fall because the title made me think it might be helpful for processing some grief. That turned out to be true.

L’Engle writes about the death of her mother (her grandchildren’s great-grandmother), her mother’s life, her decline at L’Engle’s country home, and saying goodbye. I expect to revisit this book in the future.

2. Louisa May Alcott: A Biography by Madeleine B. Stern

This biography absolutely absorbed me. One of the most engaging biographies I’ve read (a list that continues to grow), and I learned a lot. One big takeaway: Little Women is not nearly as autobiographical as I thought. It’s more a fantasy of what Alcott’s childhood might have been if her father was a more consistent, reliable provider. Instead, he got sucked into all sorts of ideological fantasies that didn’t line up with the practical reality of being poor in the northeast in the 1800s. Louisa ultimately became the family’s sole provider.

One scene in particular that has stuck with me since reading this book takes place after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, which required escaped slaves to be returned to slaveowners even if they’d made it to a free state (the Alcotts were abolitionists):

“In June, Louisa saw Boston stricken with a more direful woe than even her own had been. Father had courageously joined with the members of the Vigilance Committee to rescue the fugitive Anthony Burns from the courthouse, but the attempt had failed, and on the second of June the slave was returned to his owner. Standing on Court Square, Louisa saw the houses draped in black, the sidewalks a seething mass of people hissing and hooting the troops who passed back and forth. All flags hung Union down. As the procession moved on, Louisa caught a glimpse of the fugitive’s face, scarred by a burn or a brand. There was no martial music in this parade, only the rumble of angry throngs, only the clank of scabbards and the dull tramp of marching feet. Surely this rendition would one day be redeemed. Remembering another fugitive at Hillside, Louisa hoped that she would have a part in the redemption, when pistols would be cocked not at the slave but at his owner.”

3. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft

Probably the most challenging book I read all year, simply due to the 18th-century tradition of really long sentences, Vindication was also incredibly relevant. Every argument Wollstonecraft makes in favor of recognizing woman’s full humanity could be quoted in modern debates regarding gender. This is, of course, an indictment of modern society — we’re not as advanced as we think — but also: no need to stutter. Just quote some Wollstonecraft. Along with her arguments for woman’s rights, I appreciated her salty tone toward high society.

Here are a few favorite lines:

- “It is justice, not charity, that is wanting in the world.”

- “There is a homely proverb, which speaks a shrewd truth, that whoever the devil finds idle, he will employ. And what but habitual idleness can hereditary wealth and titles produce?”

- “Strengthen the female mind by enlarging it, and there will be an end to blind obedience; but, as blind obedience is ever sought for by power, tyrants and sensualists are in the right when they endeavour to keep women in the dark, because the former only want slaves, and the latter a play-thing.”

I enjoyed this work so much that I wrote an entire essay on Wollstonecraft for Women’s Barbell Club.

4. Amelia Bloomer: Journalist, Suffragist, Anti-Fashion Icon by Sara Catterall

Top contender for favorite biography I read this year, Amelia Bloomer is an up-close look at the life of the temperance advocate, suffragist, founder of The Lily, and sort of accidental dress reformer (that’s where the bloomers come in). Bloomer played a significant role in the women’s suffrage movement, including introducing Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony to each other. Bloomer joined the cause for suffrage when it became clear that the men in office wouldn’t pay attention to the issues that concerned women — especially temperance, which women pushed for to combat domestic violence that they saw as downstream from alcoholism.

Some of Bloomer’s own words:

“None of woman’s business, when she is subject to poverty and degradation and made an outcast from respectable society! … None of woman’s business, when her children are stripped of their clothing and compelled to beg their bread from door to door! In the name of all that is sacred, what is woman’s business if this be no concern of hers? … None of woman’s business! What is woman? Is she a slave? Is she a mere toy? Is she formed, like a piece of fine porcelain, to be placed upon the shelf to be looked at? Is she a responsible being? Or has she no soul? Alas, alas for the ignorance and weakness of woman! Shame! Shame on woman when she refused all elevating actions and checks all high and holy aspirations for the good of others! … Public sentiment and law bid woman to submit to this degradation and to kiss the hand that smites her to the ground … Let her show to the world that she possesses somewhat of the spirit and the blood of the daughters of the Revolution!”

5. Platonic: How the Science of Attachment Can Help You Make and Keep Friends by Marisa G. Franco

Maintaining friendships in Denver has been a challenge for all 8.5 years I’ve lived here. People come and go, or they disappear without a word. It doesn’t help that friendships have felt pretty precarious most of my life. It’s easy to get stuck in the mental loop of “no one wants to be friends with me, so I don’t want to be friends with anyone, so no one wants…” — which is wild because I like people a lot.

This summer, I decided to enlist some help by reading about friendship. I picked up a couple books from the library, ended up reading this one first, and it was so helpful I didn’t bother reading the other. Platonic provides helpful psychological background to why friendships can feel so treacherous, while offering practical steps to pursue and prioritize friendship. I left this book feeling hopeful, and I think I’ve been able to hold friendships in a more open-handed way since. Which is not to say I’m a secure friend — I still have moments of panic when a good friend says or texts something that spurs my brain toward “she doesn’t actually want to be friends with me; she’s just being nice.” But I’m better able to identify — either in the moment or when it passes — that I’m projecting onto the situation.

Some quotes I noted:

- “Growth is bending toward security [secure attachment] even if total security eludes us.”

- “Conflict is one of the only times we get honest feedback about ourselves. Without it, we obliviously cause harm.”

6 & 7. Works by Dorothy Day: Loaves and Fishes: The inspiring story of the Catholic Worker movement and The Long Loneliness: The autobiography of the legendary Catholic social activist

The political climate and my frustration at Christians seeming basically tapped out and not engaged in advocacy for immigrant neighbors, etc., threw me into looking for examples of Christian advocacy and activism that didn’t shy away from controversial issues. Perhaps at the recommendation of my Catholic roommate, I’m not sure, I landed on Dorothy Day. I read two of her memoirs, Loaves and Fishes, which focuses on the Catholic Worker movement, and The Long Loneliness, which is her spiritual autobiography. In both works, I found a kindred spirit and way of thinking about the world and our part in it.

Dorothy Day was a socialist-turned-Catholic whose convictions led her to live a life of service, working and living with the poor and destitute in New York City. Her memoirs contain written portraits of the people she worked closely with and her observations of poverty and reform.

Some favorite lines:

- “One of the greatest evils of the day among those outside of prison is their sense of futility. Young people say, What good can one person do? What is the sense of our small effort? They cannot see that we must lay one brick at a time, take one step at a time; we can be responsible only for the one action of the present moment. But we can beg for an increase of love in our hearts that will vitalize and transform all of our individual actions, and know that God will take them and multiply them, as Jesus multiplied the loaves and fishes.”

- “We are our brother’s keeper. Whatever we have beyond our own needs belongs to the poor.”

- “Where were the saints to try to change the social order, not just to minister to the slaves but to do away with slavery?”

8. The Stories of Edith Wharton, Volume 2 by Edith Wharton

Edith Wharton has officially landed in my favorite authors hall of fame. Last year, I included House of Mirth in my books roundup. This year, a volume of her short stories that I found at the thrift store (truly my number one source of books I love that I didn’t know exist). Every story is a masterclass in human psychology. Wharton knows human nature the way an architect knows a blueprint. Without directly explaining what’s going on, she makes clear to the reader exactly what’s happening inside her characters. I’m officially collecting her work now and plan to read another volume or two this year.

9. Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart by Nicholas Carr

I didn’t realize until after I finished this book that Carr is also the author of The Shallows, a book on what the internet is doing to our brains that I read in 2011 for college and caused me to panic about losing my ability to read books cover to cover. In Superbloom, Carr covers social media and AI, and while I didn’t panic this time, I think everyone would be served well by reading this book. Carr is an excellent writer. I’m not sure why I didn’t take notes.

10. Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Caroline Fraser

For years, I’ve wanted to read a biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder. I was a Little House on the Prairie kid: When I was about 10, I wore prairie dresses and a bonnet as if they were my normal clothes simply because I wanted to. I read all the books in the main series. It was one of my early obsessions.

Prairie Fires torches any remaining fantasies about life on the frontier.

Fraser gives a clear-eyed history of the Ingalls and Wilder families, the homesteading era on the Great Plains, and how hard life really was. Turns out, the Ingalls moved a bazillion times because their attempts to become self-sufficient where they were didn’t pan out over and over again. Most of Laura’s family, with the exception of herself due to the success of her books, died in poverty. This book is a tome, more than 600 pages long, and also delves into the life of Rose, Laura’s daughter, who encouraged Laura to write about her childhood, though not always factually.

11. Following Jesus: The Heart of Faith and Practice by Paul Anderson

A gift from my younger brother, Following Jesus is a book about Christianity from an evangelical Quaker perspective, and every time I picked it up, I came across articulations of Christianity that pretty much exactly lined up with how I would explain my faith. At some point, I told my brother I might just be a sacramental Quaker (since Quakers don’t do water baptism or communion, but I definitely do). I read this book slowly over a few months because it was so rich and I wanted to savor it.

Some lines to reflect on:

- “What if these distractions are actually the most pressing items we need to lift to God in prayer?”

- “The spiritually needy include far more than those who raise their hands during an appeal or who muster the courage to make their way forward at the end of a service. All seekers and finders need a regular setting in which to do real business with God and to bring their lives under the scrutiny of the convicting and comforting Spirit of Christ.”

- “When God wanted to communicate his saving love to the world with finality, he didn’t send us a ritual, a book, a song, or even a good sermon. He sent his only begotten Son: God’s Word made flesh (John 1:14).”

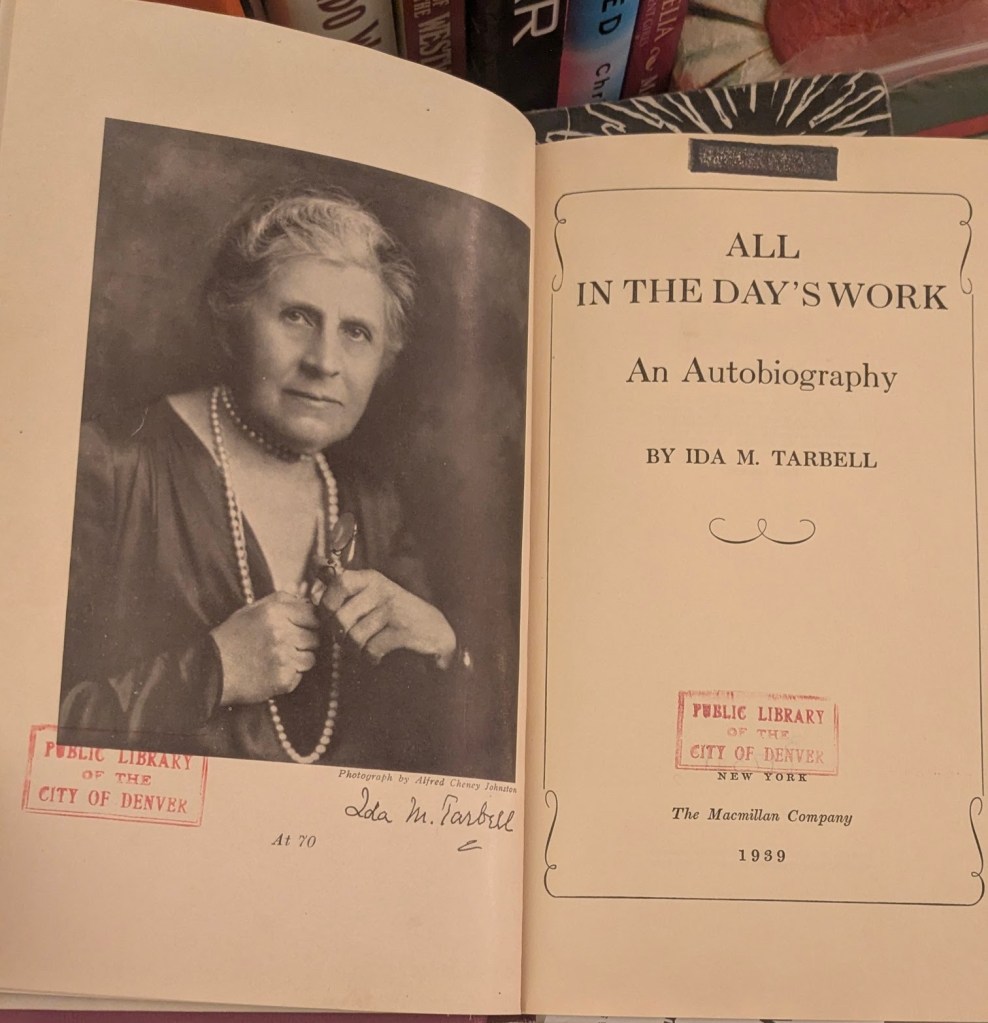

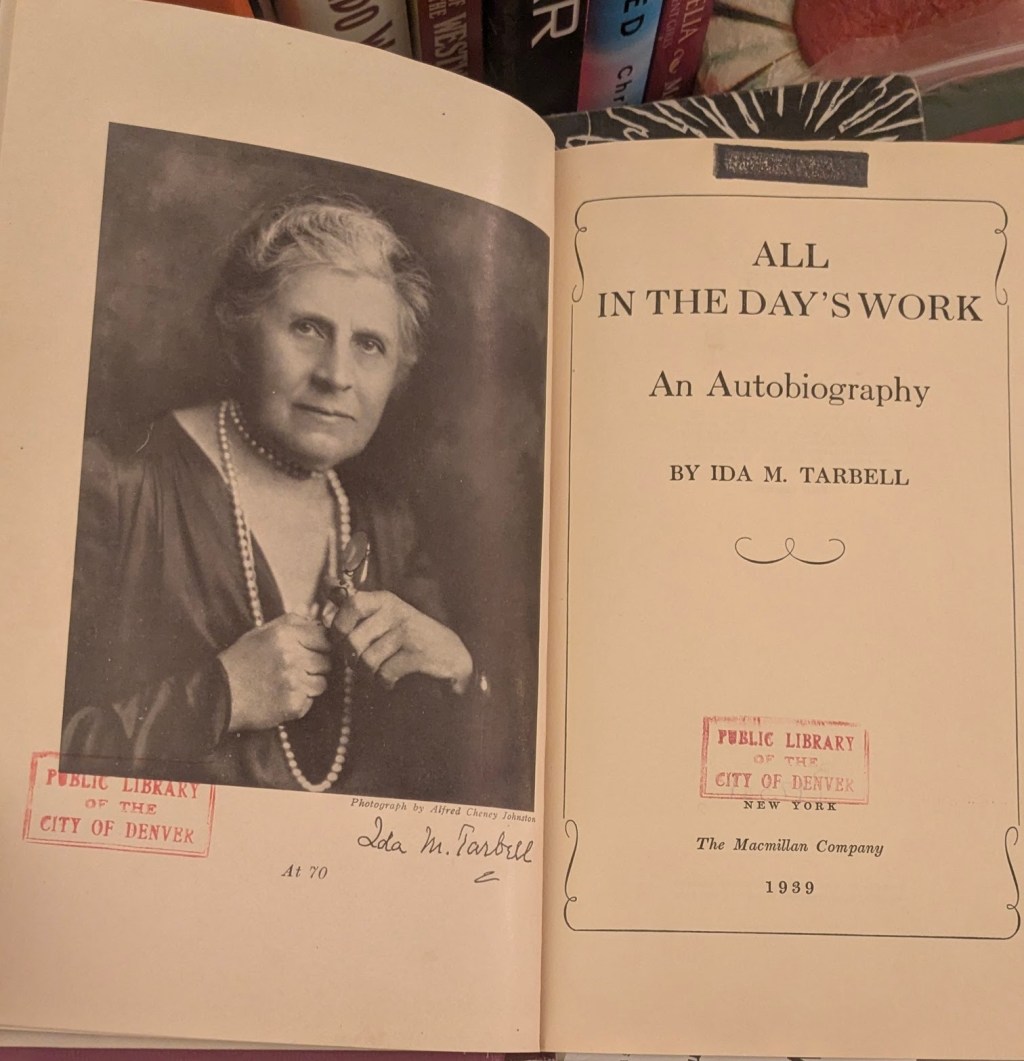

12. All in the Day’s Work: An Autobiography by Ida M. Tarbell

Of all the books I read this year, All in the Day’s Work might have the most to offer our current national moment. Tarbell was an investigative journalist at the turn of the last century. She grew up in the oil region of Pennsylvania and saw firsthand how that burgeoning industry wreaked havoc on the natural landscape. Initially wanting to pursue a career in science, Tarbell took a job with The Chautauquan, which led her to pursue journalism. She wrote for McClure’s Magazine, diving deep into the oil industry and uncovering unethical business practices. In her autobiography, published in 1939, she recounts her journalistic endeavors, shares anecdotes of the people she interviewed, and waxes poetic about her own thoughts on politics, business, and character development. Her lifetime overlapped with robber barons like Rockefeller and Carnegie, the elevation of big business and the almighty dollar in politics, and tariffs on imports that raised costs on essentials for everyday people while harming the national economy (sound familiar?). A century later, we face many of the same challenges due to basically the same faults.

Some favorite passages:

- In recounting her encounters with Senator George Frisbie Hoar (1826–1904), she says: “To save Cuba from the maladministration of Spain, to watch over her until she had learned to govern herself seemed to him a noble expression of Americanism, but to annex lands on the other side of the globe for commercial purposes only, as he believed, was to be false to all our ideals. He had the early American conviction that minding one’s own business was even more important abroad than at home.” On a printed copy of a speech, he put: “No right under the Constitution to hold Subject States. To every People belongs the right to establish its own government in its own way. The United States can not with honor buy the title of a dispossessed tyrant, or crush a Republic.”

- “Think what it would mean in Washington today if all the experimenters began where others had left off, if no demonstrated failure was repeated … if time were taken for solutions and above all if everybody concerned accepted ‘intimate and friendly’ cooperation as the most essential of all factors in our restoration.”

- “Particularly did I dislike the spreading belief that wealth piled up by a combination of ability, illegality, and bludgeoning could be so used as to justify itself — that the good to be done would cancel the evil done. What it amounted to was the promotion of humanitarianism at the expense of Christian ethics; and that, I believe, made for moral softness instead of stoutness.”

Leave a comment